CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL 2018

2nd Concert - Spiritual in Music

Mon 27.8

Our second Concert explores our dark part. That which we don't see, the spiritual, our inner struggle. The concert is choreographed as Allegri's Miserere. Parts of Messiaen's Vingt Regards sur l'enfant-Jésus are used as recitativi in this contemporary gathering of contemplation on human search for the metaphysical.

Biber's Passacaglia exposes us to one of the most striking works for solo violin with an Impressionistic feel far ahead of its time and written in a time when the metaphysical was only related to biblical texts. Arvo Pärt's Fratres transcends us to a much more contemporary notion of spirituality, a musical language and a system of thought that overcomes forms and traditions and creates its own universe of abstraction. Finally, Messiaen's Quartet for the End of Time will give this metaphysical journey a space to relate to, that of the concentration camp in which it was performed and for which it was written, and thus it will reconnect our inner struggle not with abstract thoughts but with those extreme situations in life where we seek for new meanings.

Olivier Messiaen - Messiaen - Vingt Regards sur l'enfant-Jésus No.1

8'

Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber - Biber - Passacaglia

9'40"

Olivier Messiaen - Messiean - Vingt Regards sur l'enfant-Jésus No.17

10'

Arvo Pärt - Arvo Pärt - Fratres

11'40"

Olivier Messiaen - Messiean - Vingt Regards sur l'enfant-Jésus No.7

11'

Olivier Messiaen - Messiaen - Quatuor pour la fin du temps

45'

Book your tickets

Safely book your tickets online

Light & Darkness arrow_forwardSpiritual in Music arrow_forward

Images arrow_forward

Memorial arrow_forward

Special 4-Day Pass arrow_forward

Book your tickets

- Online at ticketservices.grarrow_forward

Concert

Works

CHAMBER MUSIC FESTIVAL 2018

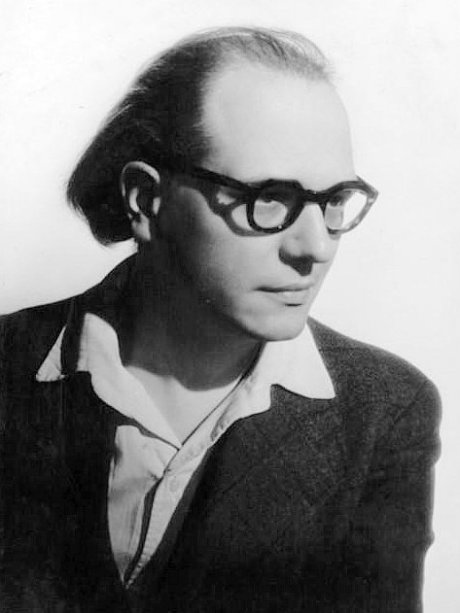

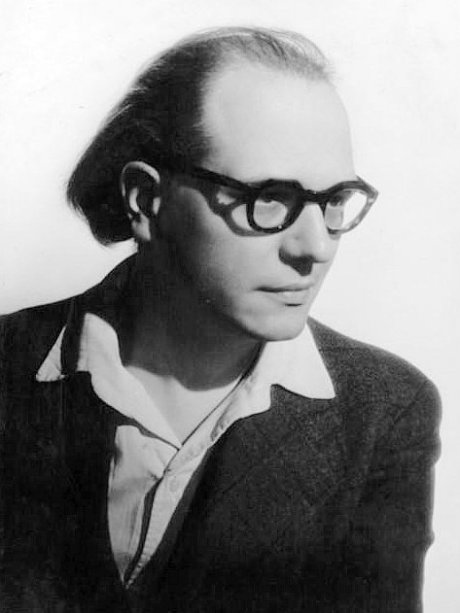

Olivier Messiaen

Vingt Regards sur l'enfant-Jésus

Olivier Messiaen’s monumental and profound work Vingt Regards sur l’enfant Jésus is one of the most extraordinary and ground-breaking works in twentieth-century piano repertoire. The fact that it was composed in 1944, when the German occupation of Paris was in its closing stages, and yet expresses such joie de vivre, conviction, love, hope and ecstasy makes it all the more remarkable. It is, above all else, an expression of Messiaen’s deeply-held Catholic faith which involved sound and silence, beauty and terror, joy, love and an all-embracing sense of awe.

All twenty movements are constructed around three distinctive themes. The first, the Theme of God, a slow-moving chordal motif, heard first in the opening Regard (Regard du Père/Gaze of the Father). It recurs in Regards V, XI and XV, and is always sonorous, luminous and profound. The second theme, the Theme of the Star and the Cross, first appears in Regard II. Turbulent and fractured, it signifies the beginning and the end of Christ’s life. The final theme, the Theme of Chords, is a sequence of four chords which are used in various ways throughout the entire work, most obviously in Regard XIV. In the final movement, all three themes are brought together.

An important aspect in Messiaen’s work is “flashes”, colourful chords and clusters of notes or fragments which reflect Messiaen’s belief that it was only possible to comprehend the totality of God in “flashes”. Silence also plays a significant role in the music, never more so than in the penultimate movement where the sonorities, resonance and sound-decay of the modern piano are utilised with highly arresting effect. In some movements, the silences are like breaths or moments of hushed contemplation. Birdsong plays a meaningful part in many of the movements too (Messiaen was a devoted ornithologist), with chatterings and squawks, trills and shrills in the upper registers, always used melodically rather than for pure effect. There are even references to Gershwin’s ‘I Got Rhythm’, a joyous, jazzy outpouring in Regard X (Regard de l’Esprit de joie/Gaze of the Spirit of Joy), and later a hint of ‘Twinkle Twinkle Little Star’.

MOVEMENTS

1. Regard du Père

2. Regard de l'étoile

3. L'échange

4. Regard de la Vierge

5. Regard du Fils sur le Fils

6. Par Lui tout a été fait

7. Regard de la Croix

8. Regard des hauteurs

9. Regard du temps

10. Regard de l'Esprit de joie

11. Première communion de la Vierge

12. La parole toute puissante

13. Noël

14. Regard des Anges

15. Le baiser de l'Enfant-Jésus

16. Regard des prophètes, des bergers et des Mages

17. Regard du silence

18. Regard de l'Onction terrible

19. Je dors, mais mon cœur veille

20. Regard de l'Église d'amour

Heinrich Ignaz Franz Biber

Passacaglia (Mystery Sonata), for violin solo in G minor

C. 105

The 15 Mysteries of the Rosary, practiced in the so-called “Rosary proce-ssions” since the 13th century, are meditations on important moments in the life of Christ and the Virgin Mary. During these processions, believers walked around a cycle of fifteen paintings and sculptures that were placed at specific points of a church or another building. In this tradition, at every point a series of prayers was to be recited and related to the beads on the rosary.

Biber's Passacaglia in G minor is part of a group of pieces composed either for the Archbishop of Salzburg, Maximilian Gandolph, Count Khüenburg (Biber's employer) or the Salzburg Confraternity of the Rosary. Finished probably in 1676, the bulk of the pieces are violin sonatas on the 15 mysteries of the rosary and are among the most important scordatura works ever written for the violin. In the original publication the piece is headed by an illustration of the what is called the Guardian Angel, in this case appearing to a small child.

The Passacaglia's opening four notes, which become its bass pattern, may refer to the traditional hymn to the Guardian Angel, "Einen Engel Gott mir geben" (God, Give Me an Angel), which has a similar tune and was published in 1666. Over the constantly sounding theme, Biber creates a series of contrasting variations of various moods before closing the piece by outlining a G major triad. It is one of the best works for solo violin before those of J.S. Bach.

MOVEMENTS

Theme and Variations

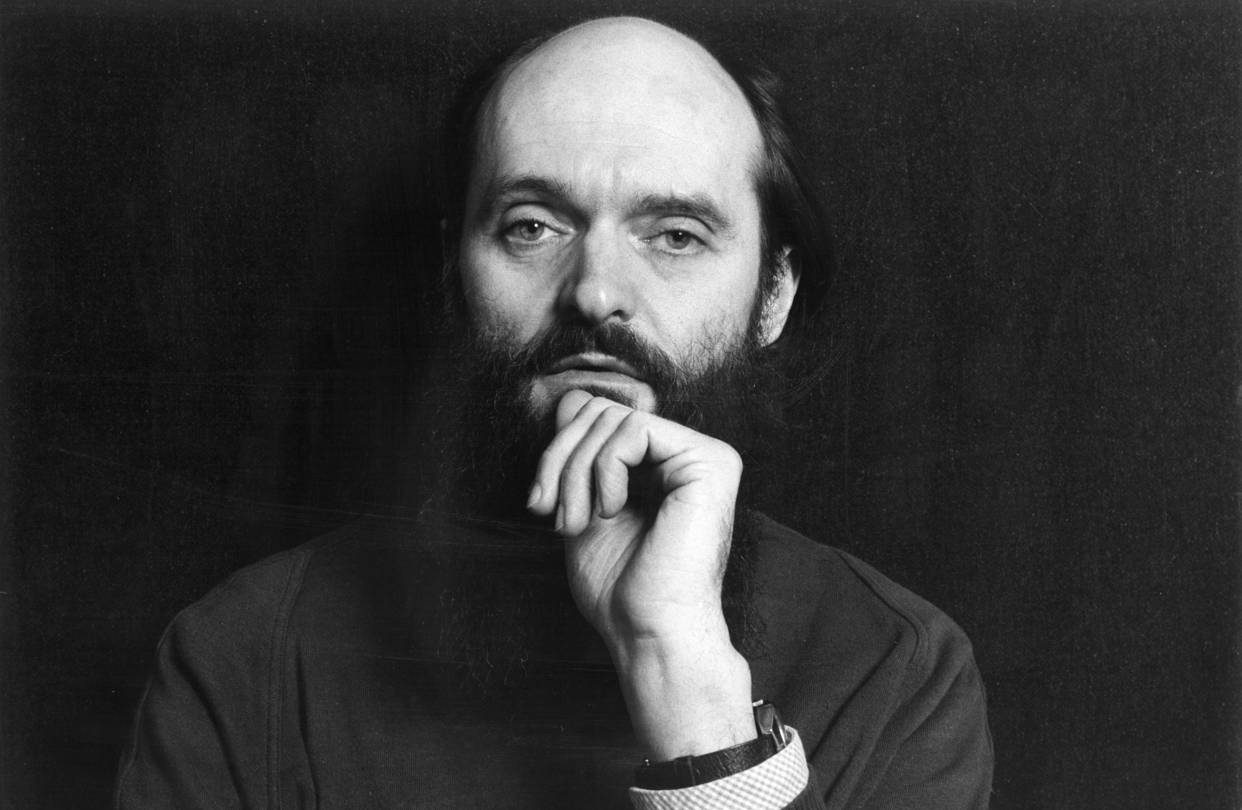

Arvo Pärt

Fratres

At the end of the 1960s, Estonian composer Arvo Pärt (b. 1935) abruptly entered into an eight-year period of compositional “silence.” When he began composing again, the music which emerged was a universe away from his earlier dissonant, ultra-complex, twelve-tone style. Its meditative mysticism recalled the timeless serenity of Renaissance polyphony while arriving at a place which was completely new. One of the first and most famous examples of Pärt’s new sound world is Fratres (Latin for “brothers”), written in 1977. It’s a piece written “without fixed instrumentation,” a characteristic which recalls the highly-adaptable music of J.S. Bach. Composed in Pärt's very own Tintinnabuli-style, Fratres allows many different settings because it is not bound to a specific timbre. “The highest virtue of music, for me, lies outside of its mere sound. The particular timbre of an instrument is part of the music, but it is not the most important element. If it were, I would be surrendering to the essence of the music. Music must exist of itself … two, three notes … the essence must be there, independent of the instruments.” (Arvo Pärt)

Olivier Messiaen

Quatuor pour la fin du temps

Quatuor pour la fin du temps (The Quartet for the End of Time) is perhaps the first of Messiaen's works in which the contrast between movements becomes truly extreme: there is a new level of violence in the music. It is not hard to imagine why this might be, given the work's famous origins, written while Messiaen was a prisoner of war at the Nazis' Stalag VIII-A camp. The struggle to not only endure the terrible conditions, but also to incorporate the experience into his Catholic faith, must have been profound. (Henri Akoka, the clarinettist for the premiere of the quartet, asked Messiaen to join him in attempting to escape; Messiaen answered: "No, it's God's will I am here.") The result is a work more emotionally engaged than any Messiaen had written previously. Messiaen dedicated the quartet in homage to the Angel of the Apocalypse, who raises his hand towards Heaven saying ‘There shall be no more time.’ The movement titles were drawn from the biblical Revelation to John. Messiaen eschewed the usual tendency of Western music for regular rhythms and metres and instead offered ever-changing, often-unpredictable patterns, frequently based on prime numbers, especially 5, 7, 11, and 13. Clarinet and violin phrases tend to be reminiscent of bird songs, and motifs recur from one movement to another. The four instruments rarely play simultaneously.

MOVEMENTS

I. Liturgie de cristal

II. Vocalise, pour l'Ange qui annonce la fin du temps

III. Abîme des oiseaux

IV. Intermède

V. Louange à l'Éternité de Jésus

VI. Danse de la fureur, pour les sept trompettes

VII. Fouillis d'arcs-en-ciel, pour l'Ange qui annonce la fin du temps

VIII. Louange à l'Immortalité de Jésus